The Fly

The common housefly, Musca Domestica, has lived alongside humans for as long as we have been human. We regard these creatures as pests. And with good reason, for although their living alongside us is commensal offering neither benefit nor harm directly, they are significant vectors of both disease and filth. Flies are valuable in the ecosystem for their work in processing decay and they have been valuable for thinking since Ancient Egypt and Greece.

Like many other creatures that are good for thinking part of the fly’s attraction owes to their inscrutable lifestyle, perhaps captured best in this short poem by Ogden Nash;

“God in (God’s) wisdom made the fly/And then forgot to tell us why.”

Flies can be vectors of fear, death, disgust, but also humor, stealth, and efficiency. Flies are ubiquitous, present throughout our cultural, natural and imaginative worlds. Perhaps most noticeably flies interrupt us; the fly in the ointment, the fly at the picnic, and the fly on TV.

It is a fly on TV that interrupted me most decisively this week. I was mostly done watching the vice-presidential debate. Susan and her father and I tuned in to see what would happen, perhaps like flies drawn to the decaying corpse of a political system. In the first few minutes of the debate I became quite anxious. I saw Kamala Harris’ forceful truth telling on display, but that was immediately contrasted by Mike Pence’s civility. He thanked the host, and congratulated Harris on her historic candidacy, overtures she had overlooked. I thought about how that would play in living rooms across the country. Over the next minutes the tone of the debate shifted as Harris named the reality of the pandemic, concern with climate change, and a slightly more adequate tax system. In response Pence painted a picture of an alternate reality of decisive response to the pandemic, deep care for people, a climate that is changing for unknown or entirely natural reasons, and economic growth. From my perspective as someone who has a radical approach to economic and military politics and is flayed out across the spectrum on social issues, it seemed clear to me that Pence was lying through his teeth in response to Harris’s statements. But I know that many believe, or find convenient Pence’s account; and I know that many found his participation more respectful throughout, even though he abandoned what I count as civility as he interrupted and talked over both the moderator and his debate opponent. The anxiety in our living room grew as this became more clear. Susan was the first to abandon the debate, putting on her headphones and gently humming to drown out the television. Arlin and I both turned some of our attention to our devices. I think he was reading the New York Times, and I was reading Twitter. By 20 or 30 minutes in we had changed the channel to The Game Show Network and were much more comfortably watching Family Feud, although cognizant of the other dramas unfolding around us. The episode ended and we tried a bit more of the debate. In the context of a discussion of the newly nominated supreme court justice Pence accused Harris of attacking religion. Harris responded, offended, and reminded Pence that she was a person of faith. We changed the channel again. In between Steve Harvey’s jibs and jabs I kept an eye on Twitter. A student of mine showed up for the first time in my feed and tweeted,

logged on for fly twitter. thank you everyone. ok bye i’m logging off again

— kalena s thomhave (@kalenasthom) October 8, 2020

For the next fifteen minutes I gleefully searched Twitter up and down finding pictures of the housefly that lighted onto Mike Pence’s head and remained there for a full two minutes. I stopped worrying about the debate, and my inability to watch it, and simply delighted in the robust, and not very robust social commentary that flowed in the fly’s wake. One particularly cutting commentary reflected on Pence’s ability not to notice things connecting his not noticing or ignoring the fly to his ignoring the ugly parts of the immigration and social policy of the last four years. But my favorite was from the evangelical superstar Beth Moore, who is not someone I ordinarily pay attention to. She said,

The whole of these United States of America, Republicans and Democrats alike, needed that fly. It was a gift from God’s celestial shore. Just a few more weary days and then. I’ll fly away.

— Beth Moore (@BethMooreLPM) October 8, 2020

I was reminded again of how the natural world of creatures, when we pay attention to it, interrupts and reorients us. I was reminded that although the next month is an important time especially for our ability to care for people on the edges of society, that my anxiety should be interrupted. I had, of course, learned all of this again last Sunday, in a different way, but it’s hard to remember.

It’s hard, in a totally delightful way, to think about way to say after a sermon like Hillary’s last Sunday. I had some options as I came into my sermon writing time. Ruth Shantz has let me know I need to preach on Zaccheus at some point this fall growing out of our book group on Jennifer Harvey’s book, Dear White Christians. I continue to reflect on some of the small miracles of church life in a pandemic. And the NBA Finals are this week and I’m not above the occasional bad sports sermon. But I also had the debate in mind when I went to the lectionary scripture, and what I found there pushed me decisively towards a sermon in which I reflect some on the reality we have in our nation now where we have at least two entirely incommensurate visions of reality to engage. Each of the stories that the passages read by Eric and Emily engage serious disagreements between individuals, communities, and nations. It’s clear that at points these disagreements reveal visions of reality that are very different.

Good Trouble, like the Good News of the Gospel, is entirely context dependent. It is always Good for some people and Trouble for some people but who those people are depends on your vision of reality. It is one thing to have a vision of reality that contrasts or disagrees sharply with other visions. I think about this a lot right now in reference to our police. Some people like the police, some people think they need to be reformed, and some people think they need to be abolished and replaced with a new structure or power in society that don’t view encounter through the lens of violence. These approaches widely different in regards to the role of the police and their connection to society and those on its edges. But they do hold some things in common: our society has police in it and the police act with force sanctioned by society. Good Trouble enters this space and asks how we care for those on the edges of society who are too often targeted by the police. Good trouble isn’t obviously reform or abolitionist, but it does demand recognizable change.

But what do we do when our picture of society doesn’t contain any common elements? How can Good Trouble do its change work when there is no agreed upon starting point. I heard Harris and Pence describe the same situations but then put those situations as parts of entirely different worlds. From my perspective, I understand how to cause Good Trouble relevant to Harris’s retreat from her earlier position on banning fracking. I don’t understand what kind of trouble approaches Pence’s denial of the human role in climate change or his insistence that the Biden Harris campaign wants to end all fossil fuel use. I know that this is much larger than the two of them. Large swaths of our population subscribe to these different visions of reality. 13 men were arrested this week with a plot to kidnap our governor and invade the state house; several of them had successful occupied the state house a few weeks ago, bringing their guns into the chambers of government.

Part of what make this space so anxiety producing for me is that I recognize that my faith is dependent on a vision of reality that is starkly different from what the normal vision of reality is. I really believe in peace, love, abundance and the voluntary baptism that inaugurates and funds all of these projects. I believe that the true reality of the universe is this one and that God is just waiting to pull away the shroud that clouds the eyes of the nations. This world that is already here and the world that is not yet, this is a contrast between two starkly different visions of reality. It’s not exactly the same contrast as between the two different visions of reality most active this month in the United States, but sometimes I wonder if the habits of thinking are not the same, or at least dangerously close. What are we to do?

It’s my job to turn to scripture to answer these kinds of questions, and this week my encounter with the lectionary felt to me like scripture was also turning to me. Which brings me to my first point.

1. Be Vigilant

Many of these points are about one or another kind of vigilance. Think about the vision of reality you are using to approach the world. Think about what you are hearing. Think about the differences. Don’t take what anyone is saying, least of all Generation X pastors with long hair, for granted. Part of this vigilance involves the 12 notes against worry that Hillary offered us last week.

2. Reject Idols

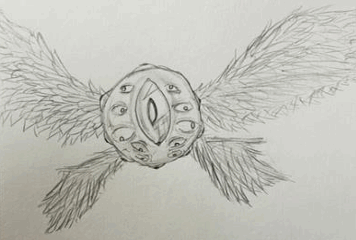

Aaron’s golden calf was a gaudy, glitzy, golden turning away from God. Today our idols might be white supremacy, liberal progress, guns, not voting, greed. It can be hard to see our ideas or agree about what they are. Good trouble is like a fly interrupting our gaze just enough to reorient our vision.

3. Work To Dissolve Disagreements when you can

I’m not surprised that we rarely name women Euodia and Syntyche anymore. They are known now mostly for having a disagreement, and disagreements need attention. Not every disagreement can be resolved. I engaged a grade school friend on Facebook after the debate when she posted, “Pence is a good man”. I tried. I think I failed.

4. Accept Invitations

The excerpts of Jesus parable of the banquet that Eric read is a strange text, and the full version is even stranger. We aren’t surprised by a parable about a banquet. God loves feasts. We aren’t surprised that the original guests don’t accept and that everyone good or bad in now invited. This message of radical inclusion is our gospel here at Shalom even when we fail to live it out.

5. Show Up

But when one of the guest isn’t wearing the right clothing and is cast out we are surprised. The casting out suggests that there isn’t a good literal meaning to this parable. The Ruler doesn’t really have access to a place of gnashing of teeth and it’s not about wearing the right thing. This is a parable of heaven, that is, a metaphor. So what does it mean when the guest has the wrong clothes? It may suggest not really showing up. If the wedding banquet is the heavenly table that God sets then it is one that we need to show up to as ourselves, but also clothed for God’s feast. This doesn’t meant we are to become something we are not, just that we have taken the time to get ready.

6. Trust in God

The Bible is full of stories of God revealing God’s way to God’s people. The picture of a table set in the midst of enemies is a common vision of this. Hard as it might be an essential part of good trouble is trusting that this table is waiting for us inside the best vision of reality we have.

7. Pay attention to Flies

Hillary had twelve notes last week. But I’ll end here at 7, also a number of completion. Amen.

0 Comments