A Day on Bierstadt Wilderness

David Klaassen | Shalom Community Church | March 14, 2021

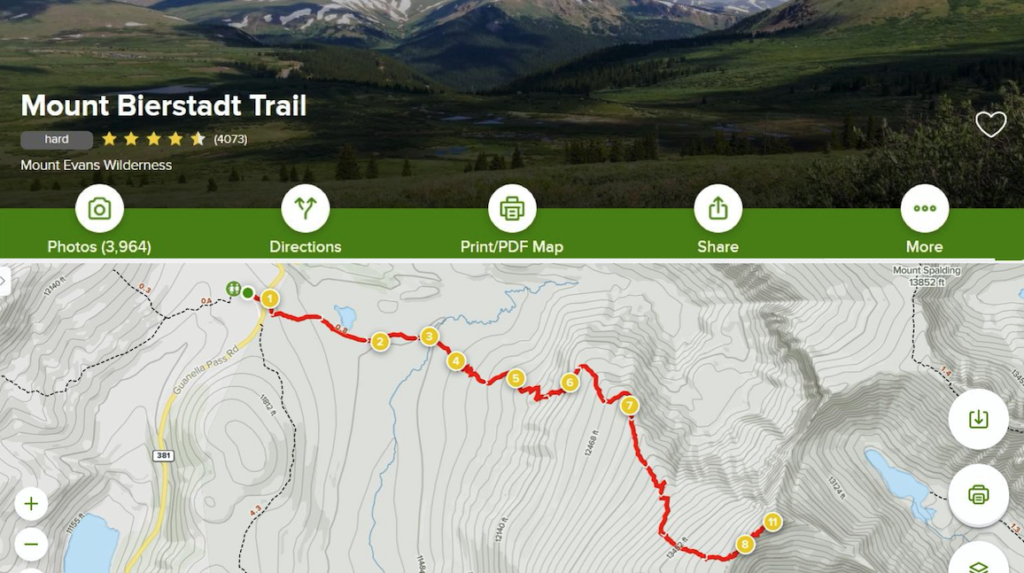

Anita and I have the wonderful opportunity of being able to spend time frequently in the house that she and Galen built in Breckenridge, Colorado about 20 years ago. We spent six weeks there last summer, long enough to do a lot of high-altitude hiking during that time. We became well-acquainted with the All- Trails phone app and learned that its red line is very helpful in keeping us on the crooked-and-narrow.

If you spend any time in Colorado you quickly learn that their world has two kinds of people: those who have climbed a 14er, and those who haven’t. 14,000 feet is less than half the elevation of Mount Everest, so let’s not get carried away with its significance, but there are 58 such peaks in Colorado – more than half the U.S. total – so there are no end of challenges: climb just one, climb them all, climb as many as you can. Some of you may have attended Rocky Mountain Mennonite Camp, which is located at the base of Pikes Peak. Many Mennonite youth climbed their first 14er in that context. Some years ago its director, Allen Bartel, climbed Pikes Peak 50 times within the year that both he and the camp were celebrating a 50th birthday or anniversary. He raised a lot of money for the camp that way.

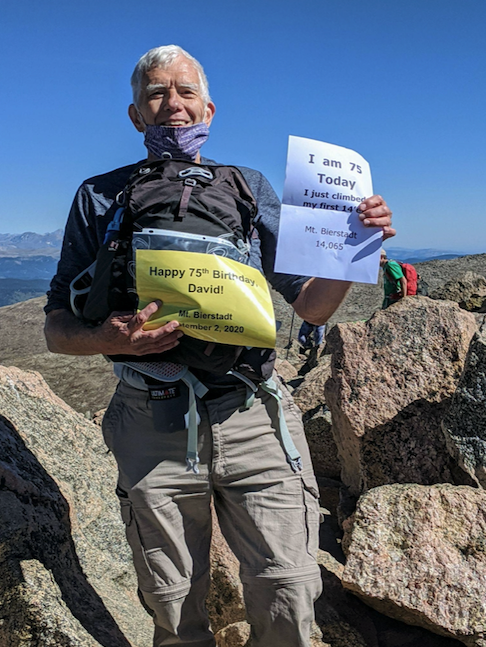

My motivation stopped well short of 50. I just wanted to join the ranks. Anita had climbed nearby Mount Quandry some years back. Her son Mark has done it many times. Even my son- in-law Troy and then-10-year-old grandson Gideon did it a few years ago. On September 2, 2020 I would turn 75, and that seemed like a good time to join the 14ers club.

Unlike Nelson Shantz in the adventure he described last week, I didn’t want to do this alone. I thought I needed a climbing buddy. Anita was in a sensible “been there, done that” mode. Fortunately, I discovered that a Colorado friend and former classmate, Paul Classen, had a similar desire to climb his first 14er. Better yet, he had a friend, Carole Suderman, who was willing to accompany us novices, providing the benefit of her mountain-climbing experience. We decided to climb Mount Bierstadt because it was reputed to be suitable for first-timers and because it was located between them and me.

We needed to arrive at Guanella Pass, the trailhead, to start our climb by 6:00am. That gave us the experience of starting under the light of a full moon. The hike is a little less than four miles one way, with an elevation gain of nearly 3,000 feet.

The AllTrails website rates it as a “hard” trail, but in truth it was more a matter of my persevering and not saying “I’m too tired” than of being physically or technically incapable of doing it. Having spent a month at 9,500 feet and doing a lot of hiking during that time was crucial – and thoroughly enjoyable – preparation.

This is the view of what we traversed, looking up from Guanella Pass at 11,400 feet, toward Mount Bierstadt, just over 14,000 feet. The first two miles were a pretty gentle rise across a wide valley – just a normal hike at altitude, but then the upward angle became much steeper, as shown when the lines on a topographical map squeeze closer together. “Be the tortoise, not the hare” as Coach Toews advised me, was the key to this segment. One other bit of sage advice needed to be modified slightly. “Just put one foot in front of the other” became “just put one foot above the other.

Many peaks have an “oops, I thought we were there” false summit. After climbing steadily to reach that ridge line where you can look over to the peaks and valleys to the east, you think you have summited.

But then the fun began. The last 200 feet of elevation were a scramble up a steep rock pile of huge boulders that had looked like a modest little bump from far below. You have to select each hand and toe hold carefully, requiring total concentration.

Realizing that there are no more boulders above you is totally exhilarating.

Then I enjoyed my 15 minutes of celebrity status thanks to a friend having created a sign saying “I climbed my first 14er on my 75th birthday” and pinning it on my back.

Total strangers were congratulating me and wishing me a happy birthday.

Why did I do it? Why do these huge masses of dirt and rock make people want to get to the top? You all know what Sir Edmund Hillary said, the first climber to conquer Mount Everest: “because it’s there.” That’s actually not a bad answer. Of course, there was the chicken who wanted to see what was on the other side. Probably almost every climber does it at least in part to test himself or herself in some way, to prove able to do it.

There is also something magical, inspirational, and spiritual about a “mountain-top experience.” That starts with the view from the top, seeing how far you’ve come. There are many Christians who can’t look at mountains without saying something like “THERE is the proof that there must be a God.” And then there are geologists who wax equally euphoric about tectonic plates and subduction – plates sliding under each other to force one up or like a really thick carpet being pushed into wrinkles on a hardwood floor.

Galen Toews, a superb physician and medical researcher, loved mountains passionately. One of his mantras was “when in doubt, go up.” Judging by the bookshelves in that house that they built, he understood almost as much about the geology and natural history of mountains as he did about human lungs. He didn’t think you had to choose between mountains being evidence of a divine creator and the product of shifting tectonic plates and volcanoes and glaciers, because those are not mutually exclusive categories. I agree. Spending extended time in Breckenridge gave me a fuller awareness of divinely inspired beauty and understanding of geological reality. It also provided sufficient acclimation to altitude to climb that high.

Mountains are everywhere in Hebrew and Christian scripture. They are mentioned almost 500 times. Perhaps only a Tabor College graduate (which would include Anita, and me) would choose to feature Mount Tabor, once thought to have been the site of Jesus’ transfiguration. Modest by Colorado standards, its prominence still symbolically represents spiritual elevation, “nearer my God, to thee.” Psalm 121 expresses that feeling: “I raise my eyes toward the mountains. Where will my help come from? My help comes from the Lord, the maker of heaven and earth.”

Three years ago I went on a “Peacewalkers on the Jesus Trail” tour of Israel and Palestine with Nelson Kraybill, past president of the Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary. We did a lot of walking, particularly in Galilee, very little of it on level ground. I left with a heightened appreciation of the holy LAND itself, as well as for people and events there over the past 3,000 years or more.

None of the mountains come close to 14er status, but they command attention from the plains below. There is beauty, looking down from the Golden Horn toward the Sea of Galilee,

and there is bleak, uninhabitable desolation near the Dead Sea.

The part of my Biblical image of wilderness that I didn’t describe today has been shaped by a favorite musical. “Children of Eden” tells the first

two main stories in Genesis – of Adam and Eve’s family in the Garden of Eden, and of Noah’s family before the flood. It is sort of a prequel to the more familiar “Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat.” The musical includes a powerful number titled “Lost in the Wilderness” that portrays the first family being banished from the beautiful, peaceful Shalom conditions in Eden that God intended as home for humankind – banished to everything that Shalom was not: a rough, infertile place that inspired what John Steinbeck referred to as “east of Eden.”

Not all of God’s creation looks like the green or snow-covered Colorado Rockies. But even the areas thought to be bleak and desolate like the area surrounding the Dead Sea, the Sahara desert, Death Valley, or featureless ocean expanses can inspire a sense of awe, inspiration, and even beauty. Anita’s grandson Henry made an interesting observation in their interview. He said he likes the wilderness because it is unspoiled by humans, a logical conclusion for someone from Brooklyn. Both the beautiful and the bleak offer the opportunity to cleanse our emotional and conscious palates of all the distractions of civilization. We need opportunities to wrestle, to test ourselves, to contemplate, to be inspired. So, thank you, God, for the wilderness.

0 Comments